A 30,000 year old GMO: On the Harm of Purebred Dog Breeding

How man's best friend became a dark reflection of ourselves — and our own hubris.

By the way, if you’re looking for a better way to hang out with A Boy and His Dog — and whoever else you follow on Substack, we really recommend using Meco. It’s free to try, cuts down on inbox clutter, and makes sure we never have to miss you too much. If you like it enough to buy, we get a small commission that lets us keep our fun facts free.

Some 30,000 years ago, we met our new best friend.

Or, more appropriately, we created them.

Dogs were born from selective breeding — a “rustic” kind of genetic engineering. Dogs were, in many ways, one of our first GMOs. A genetically modified organism, built to serve a purpose.

We don’t really know why we did. There’s several possibilities — from making it easier to hunt wild game, to pulling sleds for us before we domesticated horses or made something more bovine more cooperative.

It’s entirely possible that it was by accident — feeding wolves and other wild dogs scraps of lean meat. Eventually, they got curious, and realizing humans weren’t going to hurt them — began trusting us more.

And that they, like cats, simply got used to us — and us, to them, some 20,000 years later.

Us and cats, we’ve tolerated each other, with all our hearts, ever since.

But dogs — dogs were different.

The oldest breed still in circulation is the basenji.

This one has roots that date back to about 6,000 BCE.

It was bred with a purpose — to be a hunting dog. They’re still good at it today — agile, quick (they can nearly keep up with a greyhound: they max out at around 35 miles per hour, running full-tilt), and intelligent, they made excellent partners in the bush.

But it’s where problems with selective breeding became noticeable.

The basenji is a “barkless” dog. They don’t bark — they can’t — they make a kind of “yodeling” sound. And it’s a result of their breeding. They have unusually-shaped larynxes.

They’re physically incapable of barking, as other dogs do. And it’s because we bred them to be something other than “just a dog.”

Basenji aren’t the healthiest dogs, either. As purebreds go — especially the older breeds — they’re sturdy. But they’re prone to thyroid problems and bladder stones and, later in life, very fast-moving cancers that catch up with the speedy little guys. They live, on average, about 10-12 years.

That’s not because of what a dog is, or even what the basenji is —

It’s because of how we engineered them.

A very excellent piece in the New York Times (from the brilliant Alexandra “All Dogs are Good Dogs” Horowitz) came out this month, talking about the Westminster dog show.

Those of you following along — I don’t have many nice things to say about Westminster, the AKC, or their equivalents. Much of what I say here, is why.

Horowitz is one of the people who got me interested in dog brains — she’s a cognitive scientist who, like me, began with studying people’s brains.

In the Times piece, she breaks down the genetics of purebred dogs, much better than I could.

“The average mixed-breed dog’s parents are as closely related as cousins once removed. Past this point, these dogs’ parents are full cousins, genetically speaking,” she said in the Times.

“In most breeds, a dog’s parents are more closely related than half-siblings. For about half of breeds, dogs have parents that are genetically as close as siblings, or closer.”

“Some dogs are inbred to the point that it’s as if siblings continued mating for multiple generations. Over time, these dogs will become only more inbred, potentially developing more health problems.”

She cites a study performed by researchers at UC Davis. The study found that purebred dogs have a “coefficient of inbreeding” of 0.25.

In normal-people terms, that’s an incest baby — when two siblings have a child together.

For dogs, just like people, that’s a problem — because it increases the risks of various kinds of problems, and as generations go on, the problems become more pronounced and severe.

There are several hundred health disorders related to genetics or to adherence to the standards set by breed groups that have emerged since dog pure-breeding took off in the 19th century. Most breeds we know, and love, today — are only about 150 years old.

In genetic and evolutionary terms — that’s less than a second on the clock.

But they include changes that so drastically affect the dogs’ physiologies that they begin to have — like the English Bulldog — problems before they’re even born. The vast majority of bulldogs can’t give birth on their own — the puppy’s skull is too big for the mother’s birth canal.

Others — like the basenji — have abnormal voice boxes.

Some have connective tissue disorders. Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, a hypermobility condition, is so common in poodles its divided into Poodle Type 1 and Poodle Type 2, in dogs.

Pugs are well-known for their prone-ness to eyeballs popping out of their sockets and a host of problems with breathing — but all brachycephalic (short-muzzled) breeds have similar issues, and there’s 24 breeds with brachycephalic confirmation — all the short-faced breeds.

And despite all their issues — they’re still among the most popular purebred dogs.

In 2017, the American Kennel Club listed:

Two brachycephalic breeds (French Bulldogs and Bulldogs) in its top 10 most popular breeds.

Eight brachycephalic breeds (French Bulldogs, Bulldogs, Boxers, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, Shih Tzus, Boston Terriers, Mastiffs, and Pugs) in the top 31 most popular breeds.

Part of the overbreeding problem is breed confirmation — required for dogs shows.

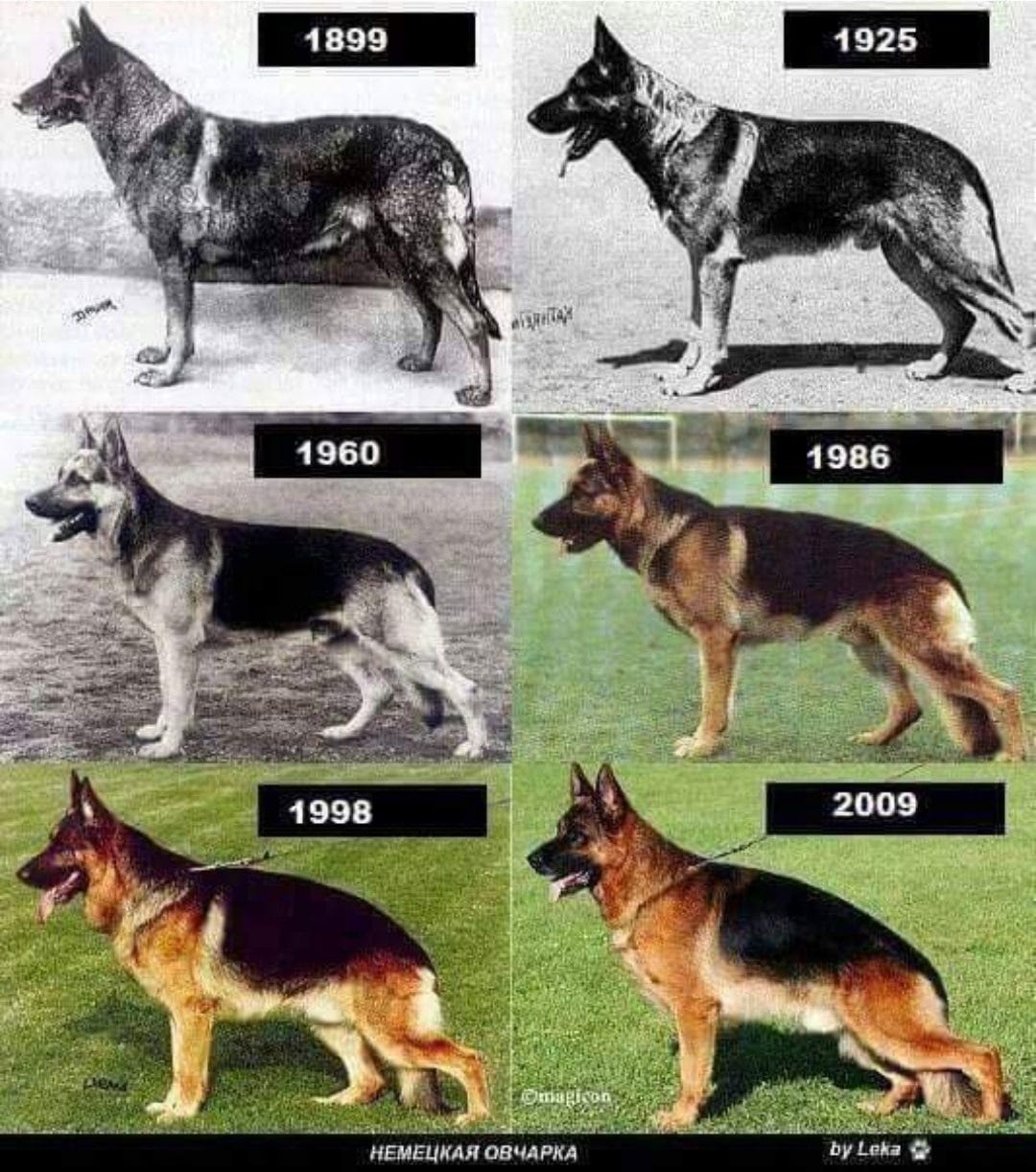

Breed confirmation is about a dog being the “perfect” example of whatever breed it’s supposed to be, from its height to its weight, to the shape of its face, or — like the German Shepherd — its back.

Zee Germans

For a wide variety of dog breeds — there are two “lines,” a dog can descend from. A working line and a show line.

Show line dogs are engineered to fit into a breed standard ideal. They’re built to appear, or to “show” better.

Because of very specific breed standards, over time, dogs have been bred that have an easier time conforming to them. The German Shepherd is just one case.

Way back in the day, there was a German ex-cavalry officer and veterinarian named Max Emil Friedrich von Stephanitz.

Max believed, unlike even many of his contemporaries involved in breeding dogs, that dogs should be bred for working. He believed they were healthier, stronger, happier dogs when they could be at their physical peak — and have a job they could perform well.

His very first German Shepherd is the first dog in the pic just up there — a majestic boy named Horand von Grafrath.

Max was a little extra about naming his dogs, I don’t know what to tell you.

Horand was bred from older German and Belgian shepherding stock. He was a strong, powerful dog, with a wide, stable natural stance, with those powerful back kickers that could launch him toward a sheep before you can say gesundheit, Herr von Grafrath!

And apparently he was quite a dog. Max wrote about him, praising him as being what he felt was the truest of breed standards — the parts that make a dog a good partner for working and for a companion.

In The German Shepherd Dog in Word and Picture, first published in 1923, he described — and arguably eulogized Horand — in his ideal of the German Shepherd:

“[Horand was] a gentleman with a boundless zest for living. Although untrained in his puppyhood, nevertheless obedient to the slightest nod when at his master's side; but when left to himself, the maddest rascal, the wildest ruffian and an incorrigible provoker of strife.”

“Never idle, always on the go, well-disposed to harmless people, but no cringer, mad on children and always in love. What could not have become of such a dog, if we only had at that time military or police service training? His faults were the failings of his upbringing, and never of his stock. He suffered from a suppressed, or better, a superfluity of unemployed energy, for he was in heaven when someone was occupied with him, and then he was the most tractable of dogs.”

He spoke very little about what the dog should look like, because the German was bred not for show — but for the farm and fields. And looked very much like their Belgian cousins (all of them — from the similar Malinois to the fluffiest of shepherds, the Tervuren.

The show standards started later, valuing what owners love to tout as a 3-point stance — the signature showing where the dog is slightly crouching on its hind legs. The standard valued the angulation (the profile of the dog’s back sloping downward) that, over time, breeders began selecting shepherds with a slope to their back, resulting in the biggest difference between working line and show line shepherds today.

Show line shepherds are “roach-backed,” with natural sloping to their backs.

And Max would’ve hated it. Horand probably would’ve made fun of them at the dog park. In German.

In The German Shepherd Dog in Word and Picture, Stephanitz castigates examples of the breed that conform to that standard — and wouldn’t breed them into his working stock.

He felt the high-line (or show-line) dogs were “over-built,” “weak,” and “faulty.” He published numerous diagrams, photos, and illustrations of their skeletons, that exhibited the correct design of their bodies — much more dog-like, or even wolf-like, that had strong hind legs, and walked with their metatarsals (their toe bones) perpendicular to the ground. That, unlike the tippy-toe three-point stance.

He went so far as to say that dogs that conform to what are American (and German) show lines today — are no longer shepherd dogs. They’re unsuitable for performing the work they were bred to be best at.

There’s something to what Stephanitz said, too — because show-line shepherds today are very prone to degenerative myelopathy (DM). DM is a disorder of the spine that’s caused by compression of the spinal vertebrae over time. It’s a progressive disorder, very difficult to treat (even in humans, let alone dogs), and causes many show-line shepherds to become paralyzed or incontinent long before they should be.

Working lines — especially very traditional German stock or shepherd stock imported to the U.S. and U.K. that stayed at work in the fields and taking their people on hunting trips and long, scenic hikes — still maintain Horand’s mold.

And they are much healthier, sturdier dogs that show-line dogs.

They’re prone to hip dysplasia (a disorder where the head of the femur, the leg bone, is too big for its hip socket, and constant rubbing wears away the bone and cartilage, leading to arthritis and/or frequent dislocations) too —as are all bigger dogs.

Working dogs as a whole are prone to it. Working stock are much less prone than show stock — and it’s arguable that’s as much as a result of their near-infinite energy levels and love of leaping and jumping and fast direction changes as much as anything else. A true working dog puts a lot of miles on their joints.

Show lines that are more gently exercised (compared to the all-day, every-day life of working dogs) still develop it earlier on average.

Because working stock is bred to work. A dog whose leg pops out of joint frequently — isn’t going to be good working dog, let alone happy doing his job. Dogs who show early signs of it (or are genetically screened), are left out of breeding stock.

That’s not the case with show-line dogs.

Big Brain Time

When we breed to any kind of type — working or show — we lose genetic diversity.

And despite Westminster — there are no dogs who win. Only their humans.

There are, and have been, stacks of small- and large-scale studies showing what happens when inbreeding occurs in dogs. The same things, as it happens, as in any other mammal, humans included.

Small litter sizes, high puppy mortality, higher numbers of congenital (genetic) disorders that grow in severity over generations, and shorter lifespans with more risk of severe medical problems; including otherwise-rare cancers, heart failures, and strokes.

A large 2019 study found, controlling for size, that purebred dogs lived over a year less than mixed-breed dogs did.

In essence — we trade a year of a dog’s life for a dog that looks like we want one to look. To choose their size, shape, and color.

Many purebred enthusiasts will say — well, at least you know what you’re getting with their personality!

That’s not entirely true, if it’s true at all. And there’s a strange bit of metascience to this next one.

While owners of both mixed-breed and purebred dogs report more behavioral problems with the mutts (or, as I prefer, the mighty Justadog) —

When studied without their owners’ input, there’s very little difference in any given breed of dog, in terms of behavior — and even less in mixed breeds.

Mixed breeds are, from their looks to their behaviors, just a dog (hence the name — justadogs. You like that? Made it up before my coffee.)

But what they lack in predictability, mixed breeds tend to be more neurologically healthy (and here’s where we get into my nerd area).

Dog neuroscience hasn’t been studied very long — that only really changed with the work of Dr. John Pilley and his “smartest dog in the world,” (who, really, probably isn’t) a border collie named Chaser.

The fun thing about Chaser?

She really probably isn’t exceptional. Sure, she can understand over 1,000 words and differentiate between nouns and verbs and has better spatial and analytic reasoning than a chimp (and all at about the level of your average toddler, and just a small step below being able to develop culture — god help us if the border collies develop culture. They’ll unionize).

She was picked at random, from a random litter of border collies that weren’t bred for intelligence. They were bred from a working line.

But since people took more of an interest, some very compelling evidence has come up that show breeding is creating dogs with weaker brains.

Take this one, showing that the prevalence of neurological (including spinal) problems in French Bulldogs isn’t just a common myth — it’s true. And disturbingly true.

Brain tumors were found in nearly 40% of Frenchies studied.

Brain tumors in mixed-breed dogs are less than 1%, and likely even less than half a percent. In most dogs, they range from 0.1% (one out of every thousand dogs) to 4.5%.

And French bulldogs aren’t unique. Those are neurological risks common to all brachycephalic dogs, if to a lesser extent (Frenchies are particularly prone).

And it’s not unique even to brachycephalic dogs. Golden retrievers — the standard-issue “I’m a new dog owner and want a dog, what should I get” answer?

Tend to be fairly unhealthy dogs. They’re prone to seizures (another neurological issue), various kinds of cancers, cataracts, heart attacks, and strokes — aside from musculoskeletal issues that, much like the shepherd, are more common in show lines — and “working” line retrievers are very comparatively rare.

You’ll only find working goldies in isolated areas, at this point (much like it’s more travel-sized, adorable screamer of a cousin, the Nova Scotia duck tolling retriever).

Dalmatians, famously, are prone to deafness (as are most creatures with a “spotted” gene — the spotty speedsters, Appaloosa horses, are also very prone).

Canis Rex

There are piles of examples for how show standards have changed. Chows used to have slightly longer muzzles and were less furry (and more muscular).

One of my own favorite purebreds — the Bull Terrier — have been extensively bred for more “football shaped” potato heads. Even since the heady days of Spuds McKenzie. Let alone Gen. George “Old Blood and Guts” Patton’s famed second-in-command, Willie.

The above illustrates the point — Willie (pictured with his pet general) looks much more like a modern pit bull, just with a more streamlined face, but still short and stocky. Old Spuds there has the longer, more collie-like face (collies and greyhounds were used to get rid of the "stop,’ in the nose, the dip between the muzzle and the skull), and today — they look like whole potatoes.

And this has been, not a choice of the dogs — but of humans. For no reason but aesthetics.

And bull terriers? That’s why I have a soft spot for them — they’ve gotten increasingly less healthy.

All-whites are prone to deafness (just like the dalmatians, and most other all-white dogs). While other colors are a little more robust, they’re all much more prone to early, and sudden cardiac events.

As with all predominantly white dogs — blue eyes aren’t uncommon in litters. But the AKC disqualifies them. They’re not “perfect,” for no reason except for losing the genetic lottery.

It’s not like, with all we know, and all the experience we have with breeding dogs — we can’t select for better genes for the dogs, as many of the early breeders — like Max Stephanitz — did.

We’ve found several potential genes associated with longevity in dogs. We have methods to make them more healthy (we always have — when pure breeds became too sickly, once upon a time, we mixed in healthier working or mixed-breed stock).

But instead — we’d rather choose to take a year from the dog, so they’ll look cuter for us.

And truly, that speaks less of the dogs — and much more of us.

That we take a living, feeling, thinking creature, and turn it into a consumer product.

Not the first time we’ve done that, certainly. We’ve done it to each other. What’s a dog? The breeders and alpha-trainers like to say “don’t anthropomorphize them! They don’t have feelings like us!”

Frankly?

Fuck that. And fuck them.

Because they don’t know what they’re talking about. We know dogs think — they couldn’t learn, if they didn’t think. We know dogs feel — and their brains react the same way as ours when we see people we love.

So perhaps maybe, instead of anthropocentrism — where we try to make ourselves feel better about warping and manipulating a creature from a dog into something to be carried in a purse, or show off on instagram, or be paraded around a ring — not for the dog — but for the people — we might consider, for once, sparing a thought for the dogs.

Because I would argue, as Stephanitz did, that when we start playing around with their appearance and not considering their health, their ability, their simple function as another mammal — they’re no longer dogs.

They’re just another consumer product.

And perhaps that’s why we don’t deserve dogs. They still love us. They still want to be our family, our coworkers and companions.

Despite what we’ve done to them. Played at being gods, transmogrifying them for our own hubris and entertainment.

We choose whether to betray that trust and loyalty or not. And that we choose as we do so much — and allow the kennel clubs to hold so much sway, and put out so much misinformation about dogs every year, just to justify it all?

What does it say of us?

And, if we play god — we create things in our image.

Perhaps that says the most of our relationship with our best friends.

Sorry, y’all are going to have to ride in the back. My pup already called shotgun.Gotta be quicker than that. You almost had it.

But — keep checking back with us.

Most of my writing is free — so while you don’t have to subscribe to keep up, becoming a paid supporter, buying me a coffee, following along on Newsbreak and Medium with my other writing, or simply sharing the things I write; they’re all appreciated. And they keep me writing about the wild wonders of the world.

Til next time —

Happy tails, readers.